Single ants rarely make headlines, but ant colonies are capable of incredible things. Watch them transform a pile of dirt into an elaborate ant hotel, for example, and you might think that a single mind is steering the entire colony. In fact, this may not be far from the truth, according to recent work from Daniel Kronauer’s Laboratory of Social Evolution and Behavior.

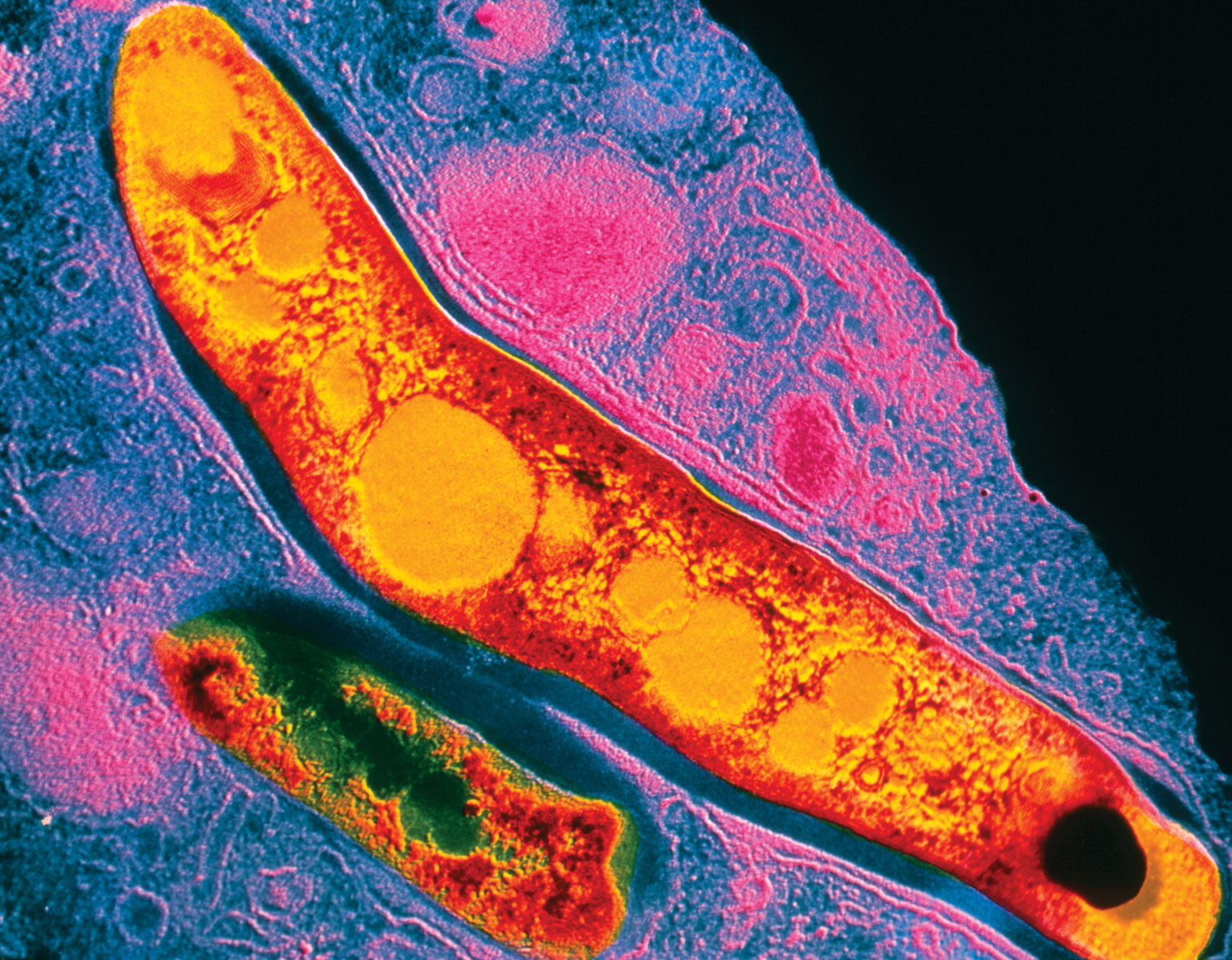

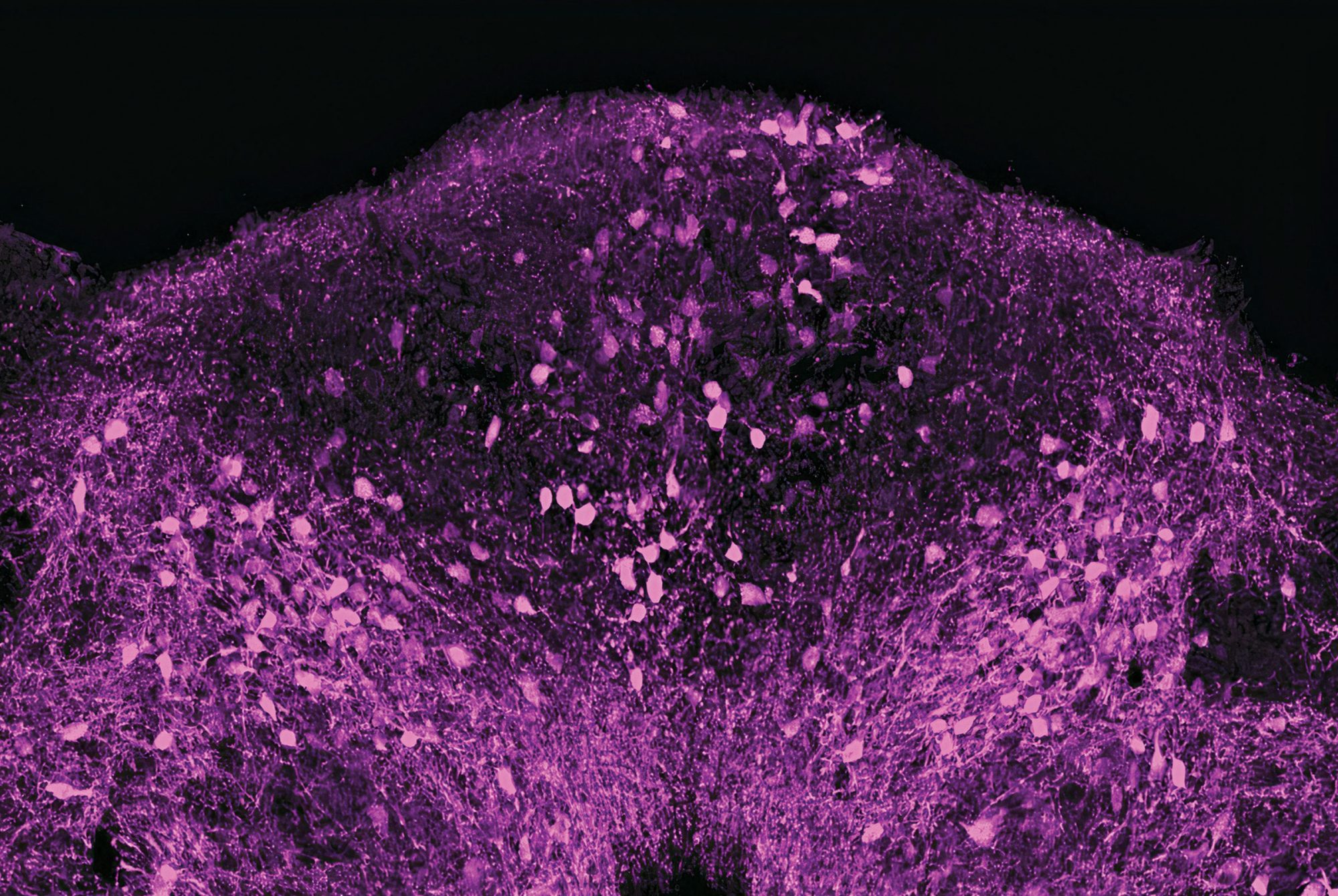

The researchers found that ants can behave in much the same way that neurons collaborate in the brain, with regard to a process called sensory thresholding. Common to virtually all animals, sensory thresholding is a kind of cost-benefit analysis in which the organism reacts to a sensory input only when that stimulus crosses a certain threshold.

For instance, sensory thresholding may be at play when you decide to move out of a hot room. The point at which you’ll get up and leave will depend partly on the rising temperature and partly on internal factors, like the body’s need to preserve energy. You may initially stay put, but once the room gets hot enough to justify the hassle, you’ll head for the door.

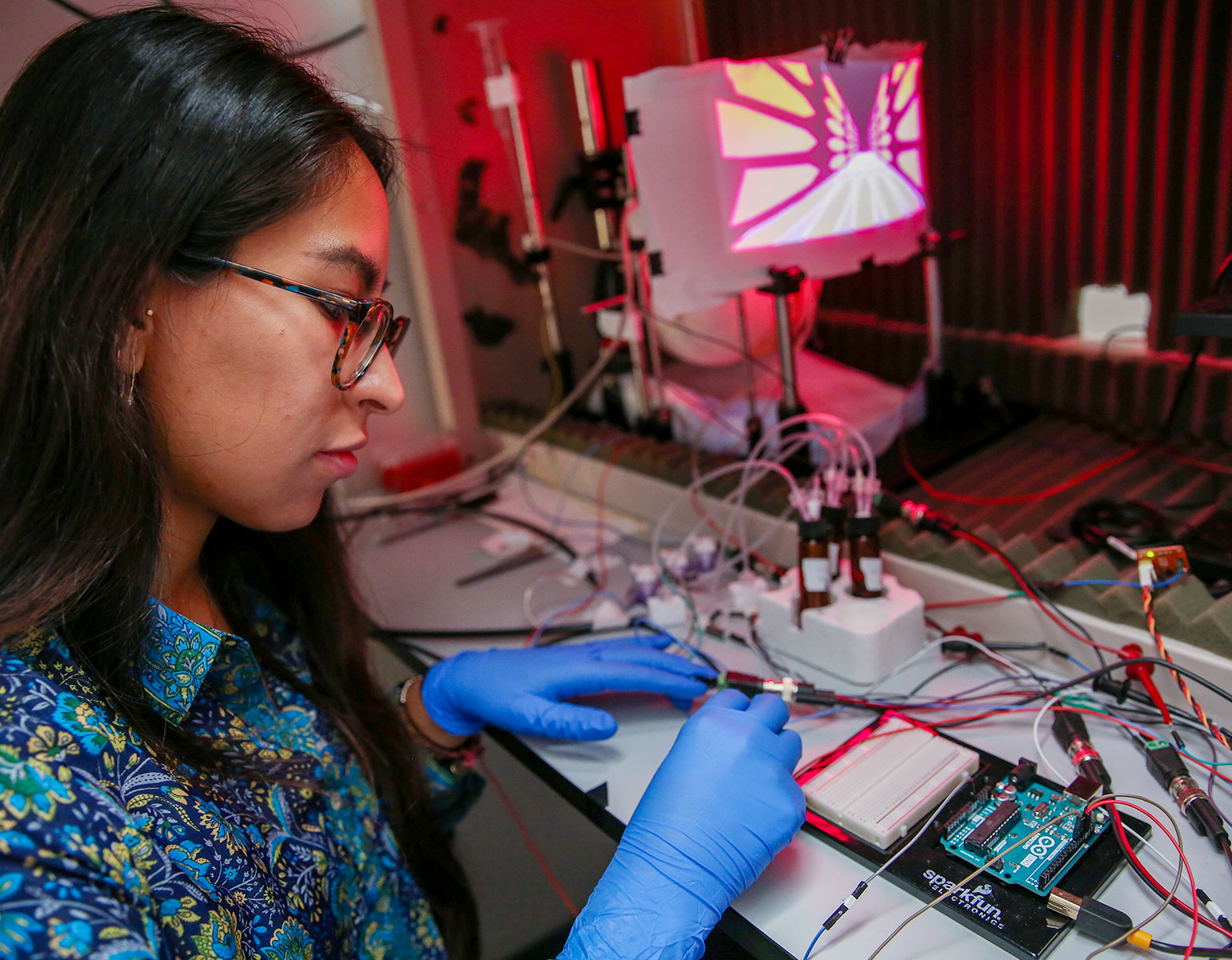

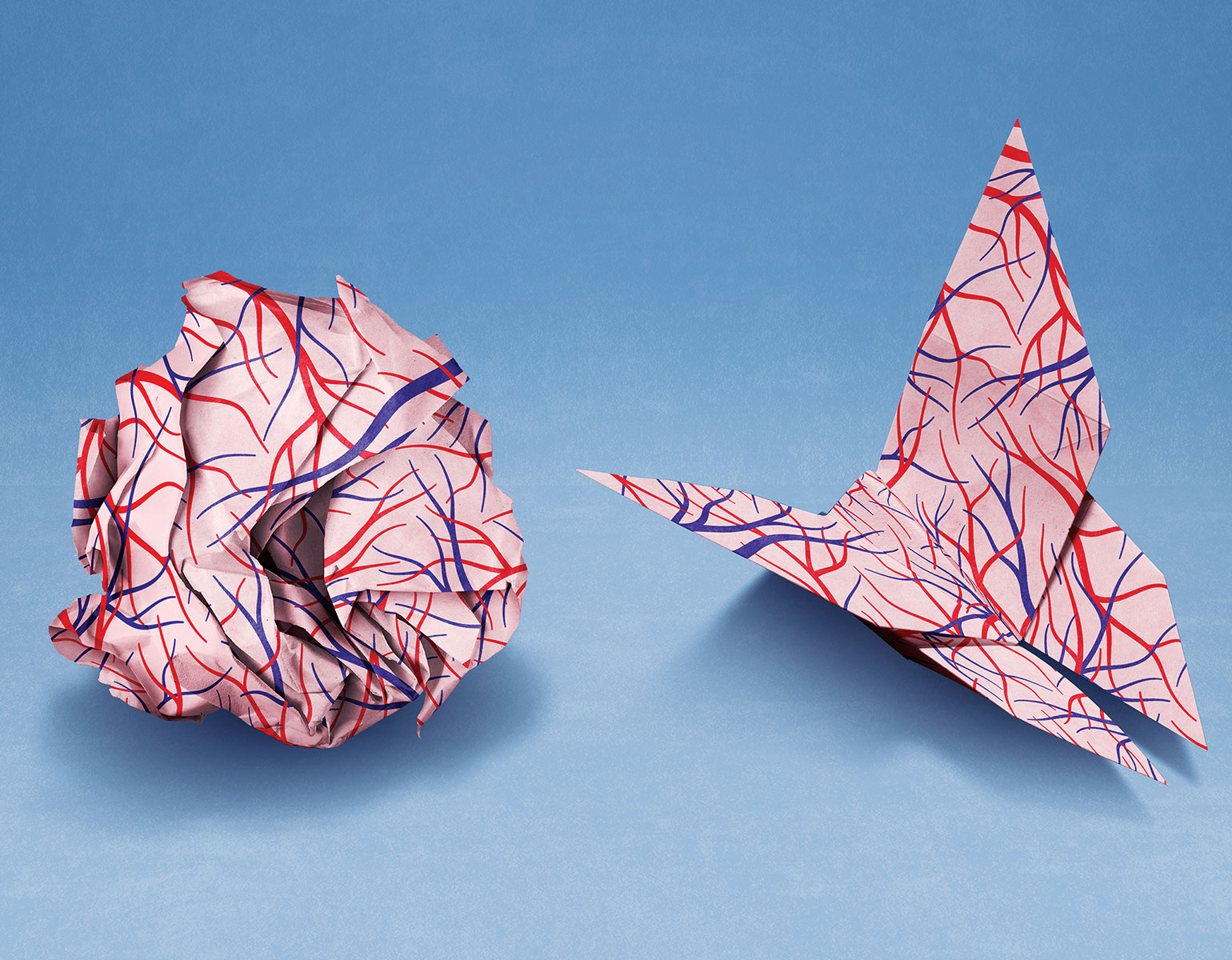

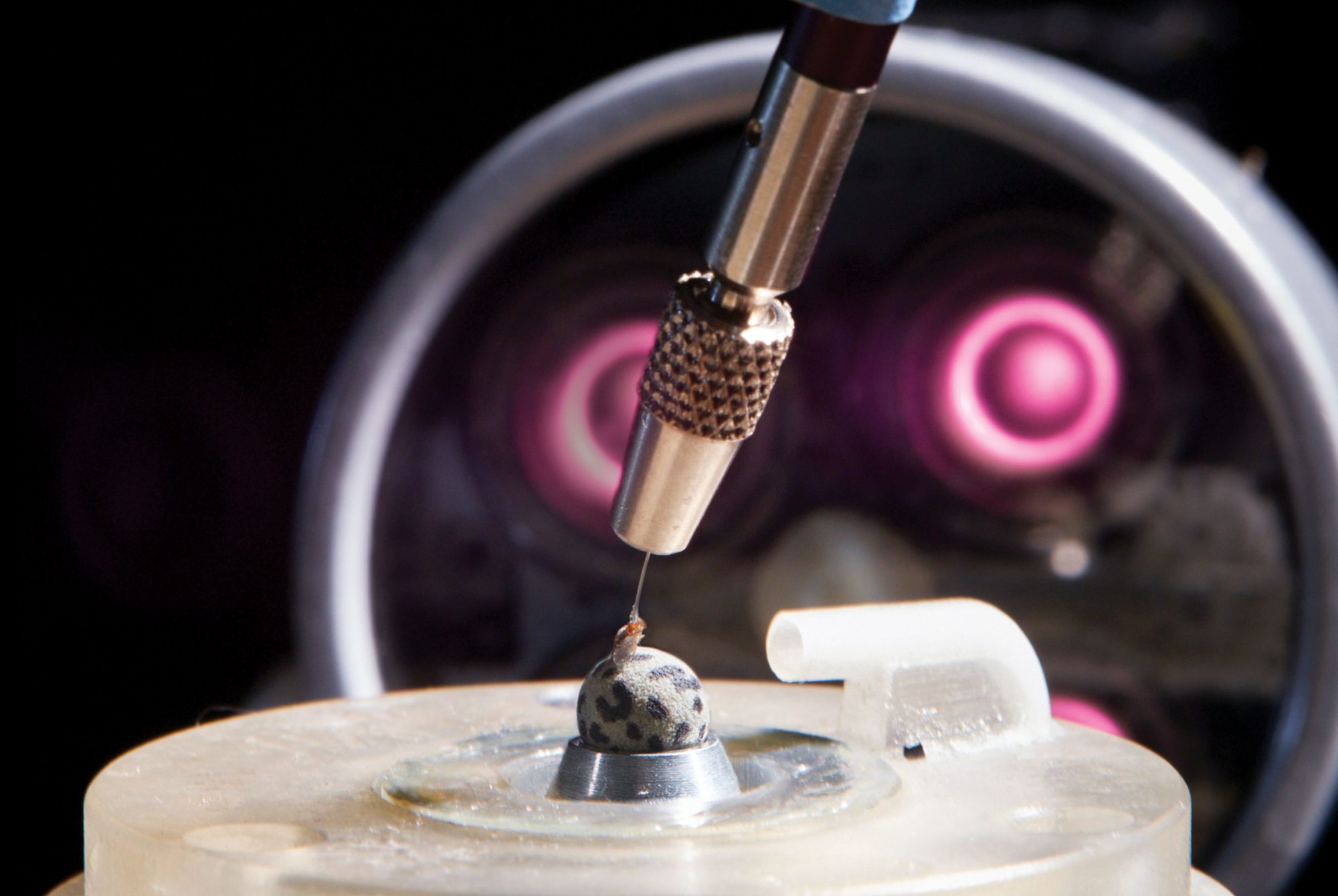

Kronauer and postdoctoral associate Asaf Gal wondered if ants would engage in sensory thresholding as a group, similar to the way neurons do in a brain—putting the needs of the whole network over that of individual cells. Working with clonal raider ants, Kronauer and Gal marked each ant with color-coded dots, let them form a nest, turned up the heat of the nest in precise increments, and tracked the ants’ responses.

Predictably, the ants fled the nest when temperatures reached uncomfortable levels, but they behaved more like a neural network than like humans shuffling out of a room. Specifically, how hot the nest had to become before the insects made an antline for the exit depended on the size of the colony: Those with around 50 members consistently fled at around 34 degrees Celsius, while colonies of 200 held out until the temperature reached 36 degrees.

This phenomenon is hard to explain if you think of ants as isolated individuals—an ant doesn’t know how many peers it lives with, so how can its decision depend on colony size? Kronauer and Gal suspect that pheromones, the messengers passing information between ants, scale their effect when more ants are present.

Still, why larger colonies require higher temperatures to pack up shop remains unclear. “It could simply be that the larger the colony, the more onerous it is to relocate, pushing up the critical temperature for which relocations happen,” ventures Kronauer, Rockefeller’s Stanley S. and Sydney R. Shuman Associate Professor.

The findings, reported in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggest that ants combine sensory information with the parameters of their collective to arrive at a group response. And according to Kronauer, the research is “one of the first steps toward really understanding how insect societies engage in collective computation.”