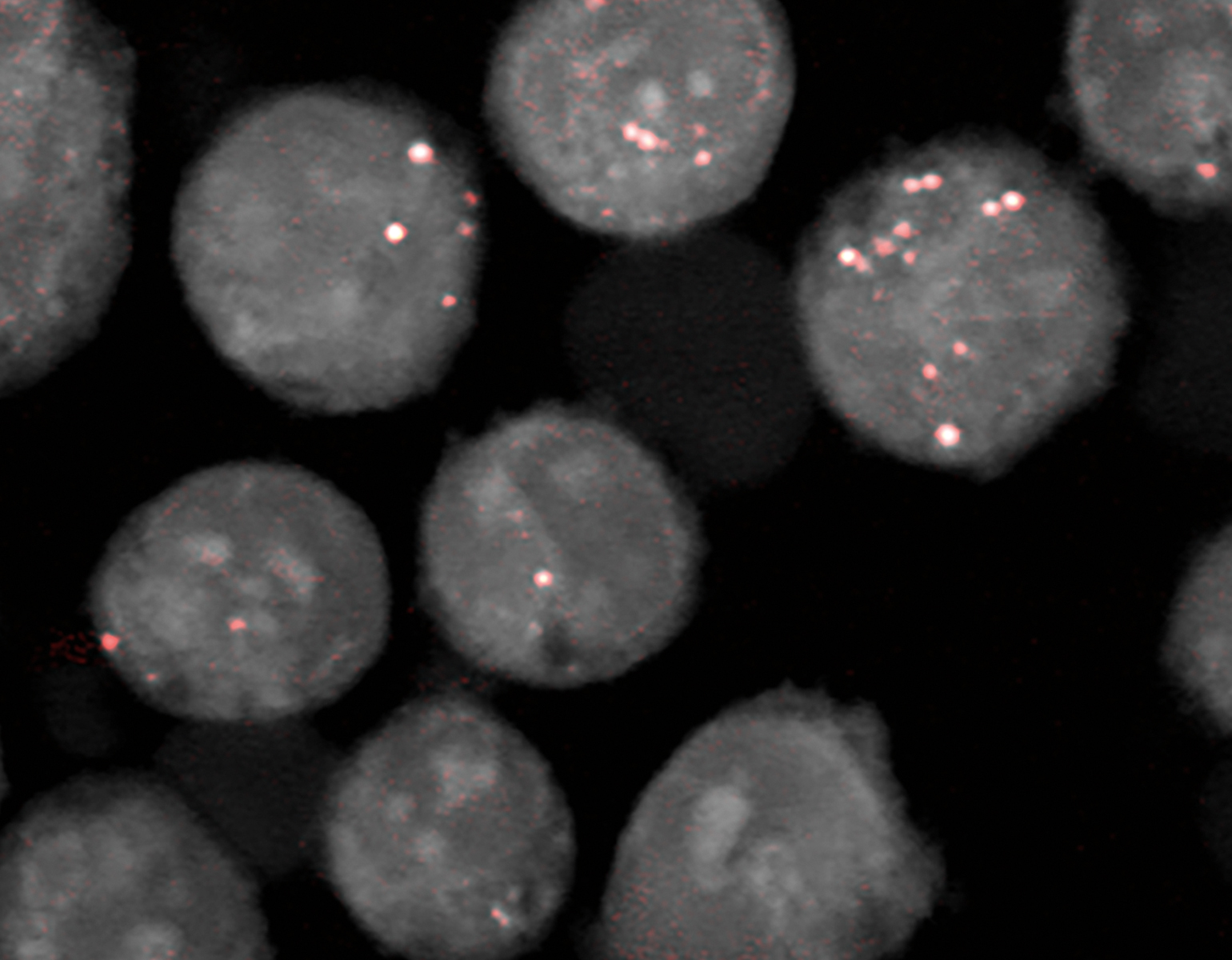

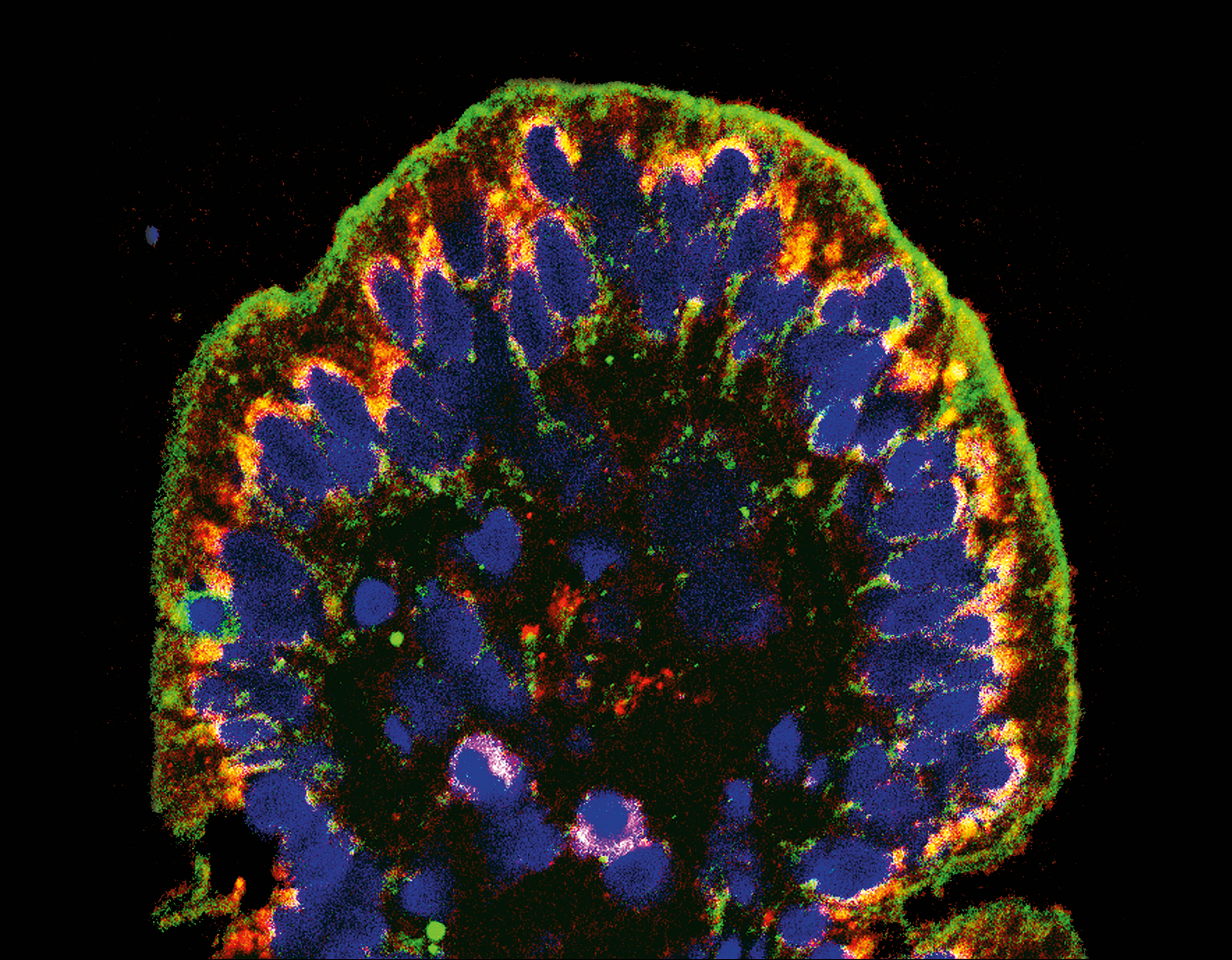

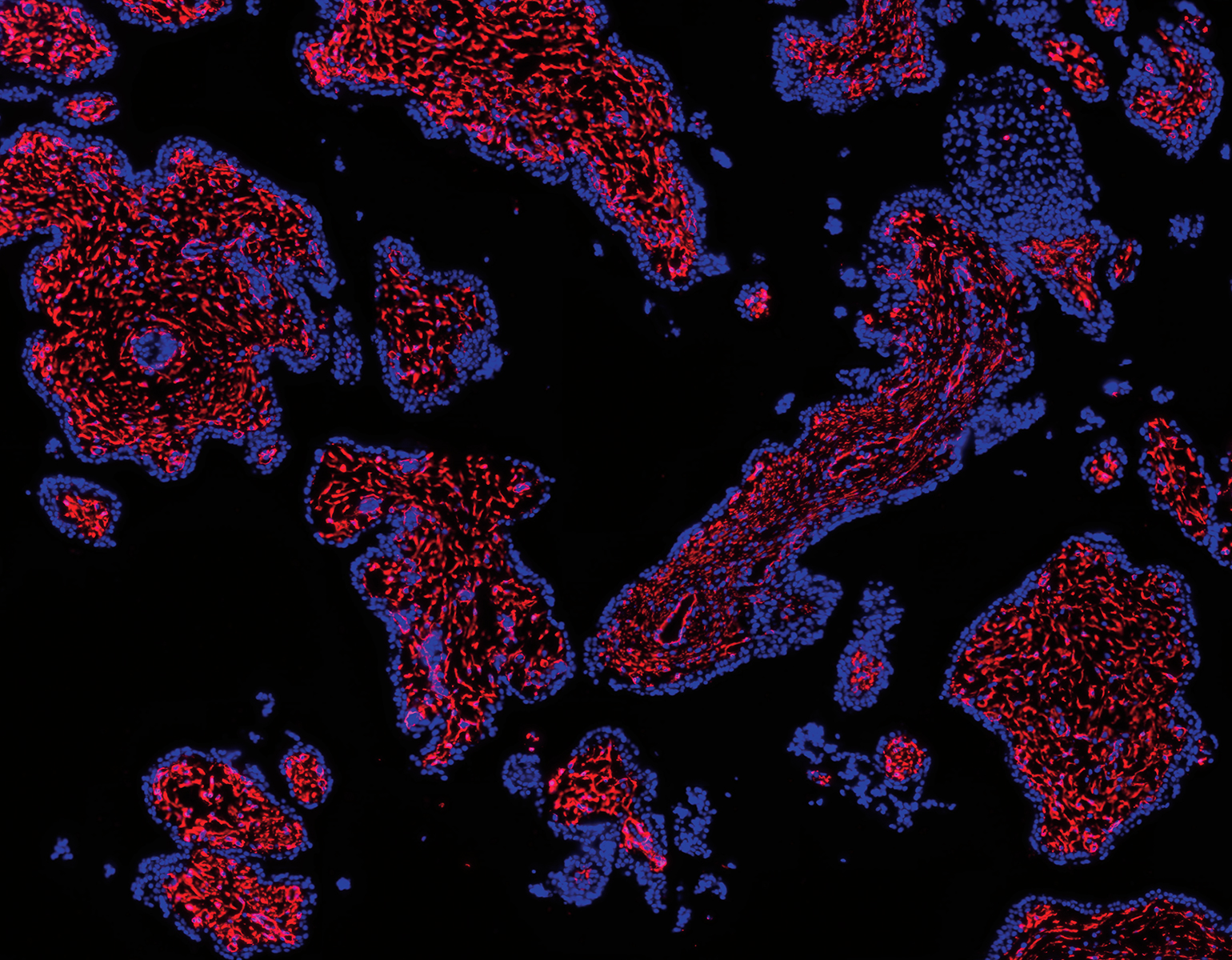

Personal growth begets neuron growth. As you learn a language or learn to hang glide, for instance, brain cells sprout new appendages, known as axons, that send signals to other cells. Researchers have long been aware of the brain’s capacity to reconfigure itself, but it is less clear how this quality, known as plasticity, supports various aspects of learning.

Data

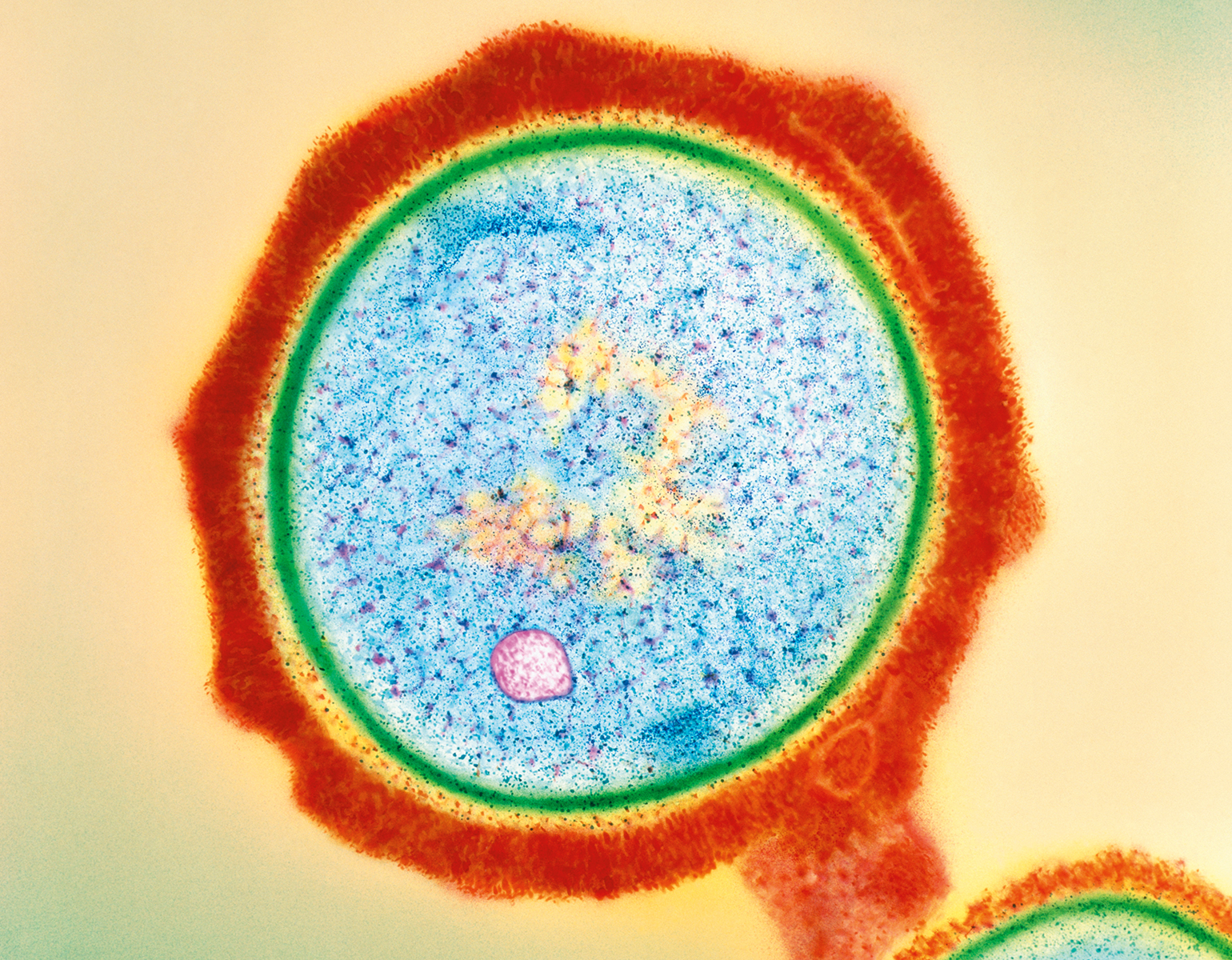

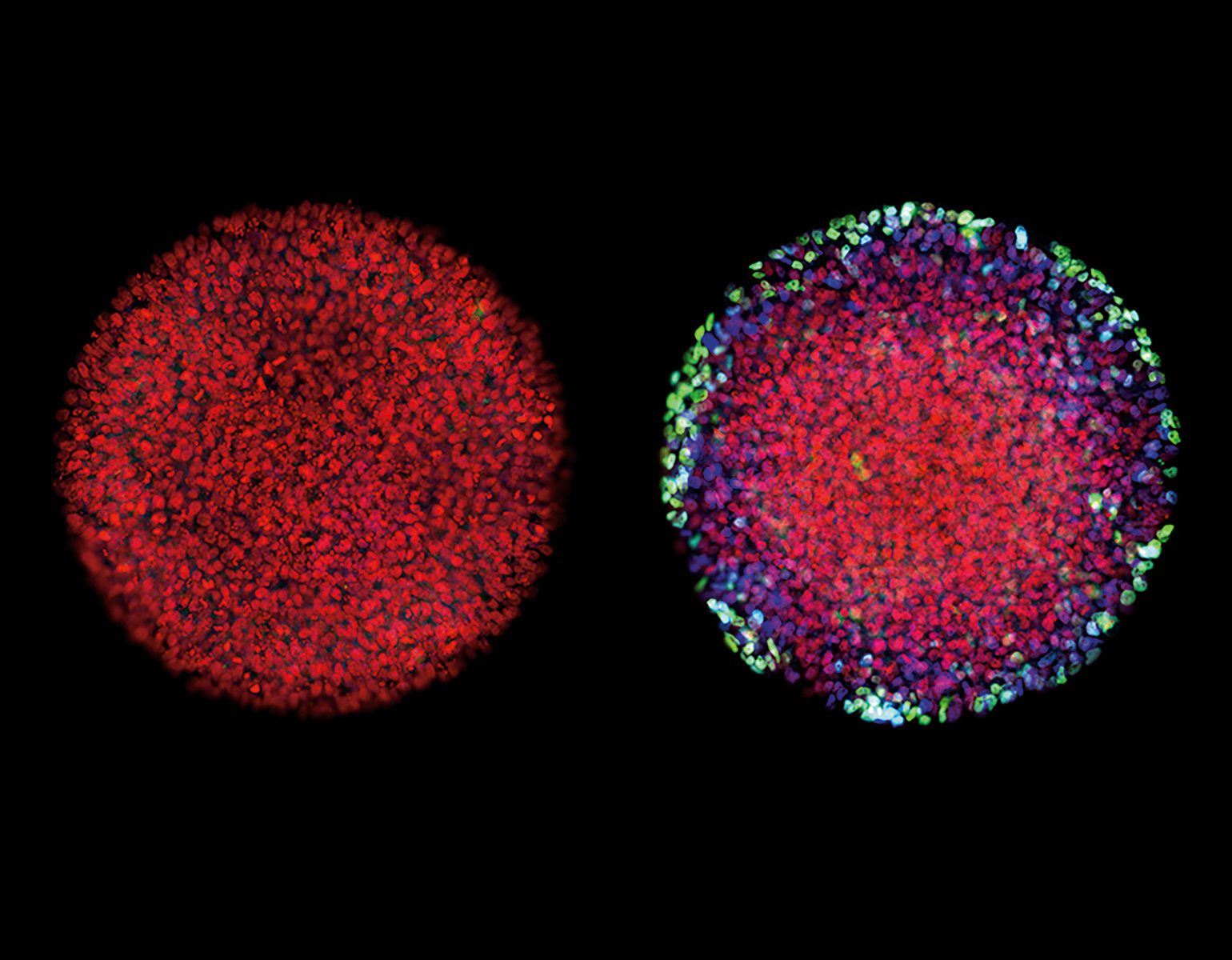

Animals have some plasticity; plants have a lot. Being able to change in response to your environment is especially beneficial if you’re rooted to the ground, hence unable to escape it.

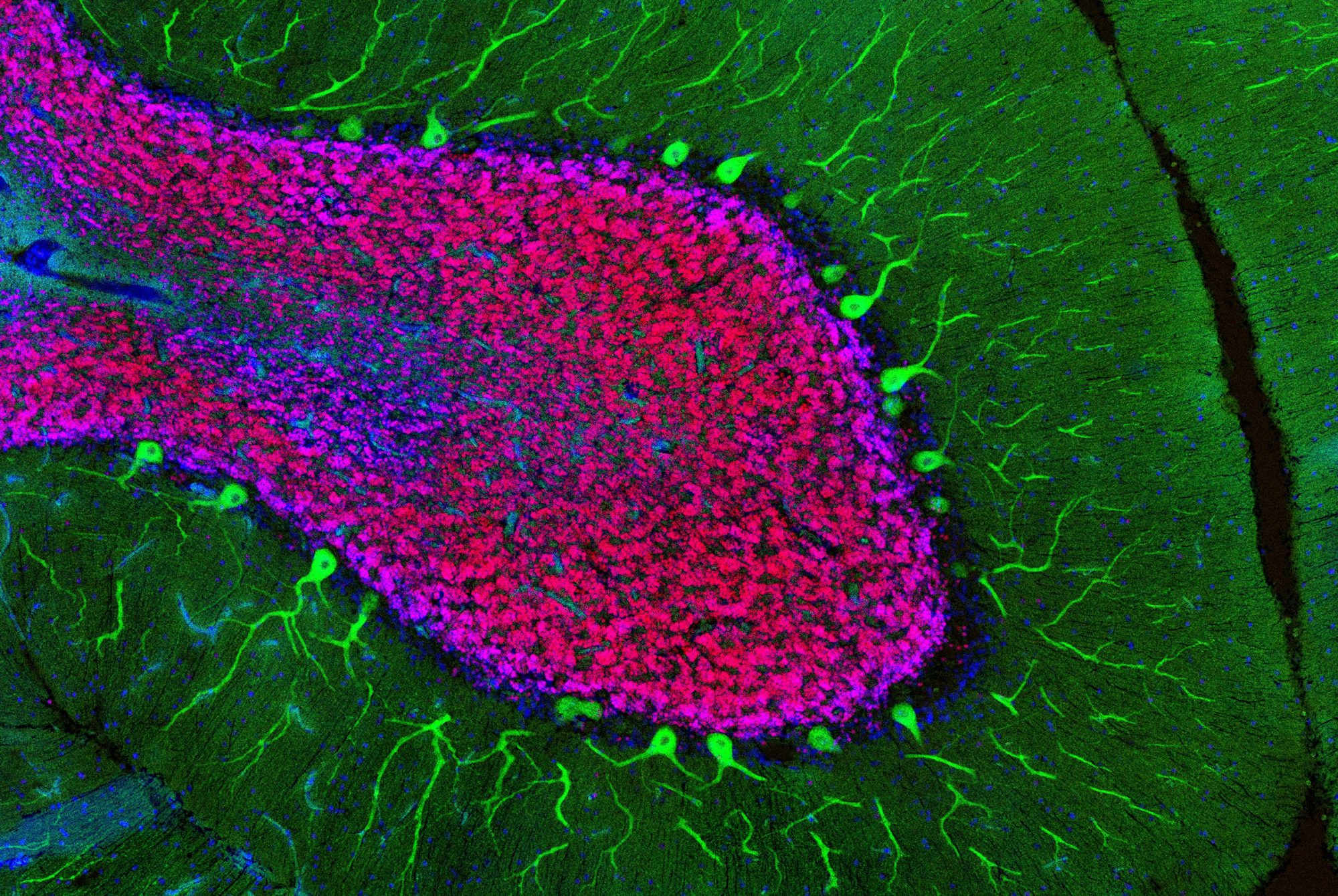

In teaching macaque monkeys new visual skills, Charles D. Gilbert and his colleagues were able to study how axons grow during perceptual learning, a process that tunes the brain to more adeptly detect certain sights, smells, or sounds. The researchers showed the monkeys busy patterns within which, with a trained eye, lines could be traced. As the monkeys got better at spotting the lines, the researchers found, their neurons grew fresh axons in the visual cortex, a brain area that processes signals received from the eye. This experiment, described in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, offers a fresh look at the precise manner in which experiences change how the brain perceives and responds to the environment.

“We’ve always known the brain needs some degree of plasticity through adulthood,” says Gilbert, the Arthur and Janet Ross Professor, “but it turns out that plasticity is more widespread than we initially thought.”