Becoming a scientist

Rachel Niec

Biologically speaking, the human gut is terra incognita. One clinician-scientist is leaving no stone unturned in exploring it.

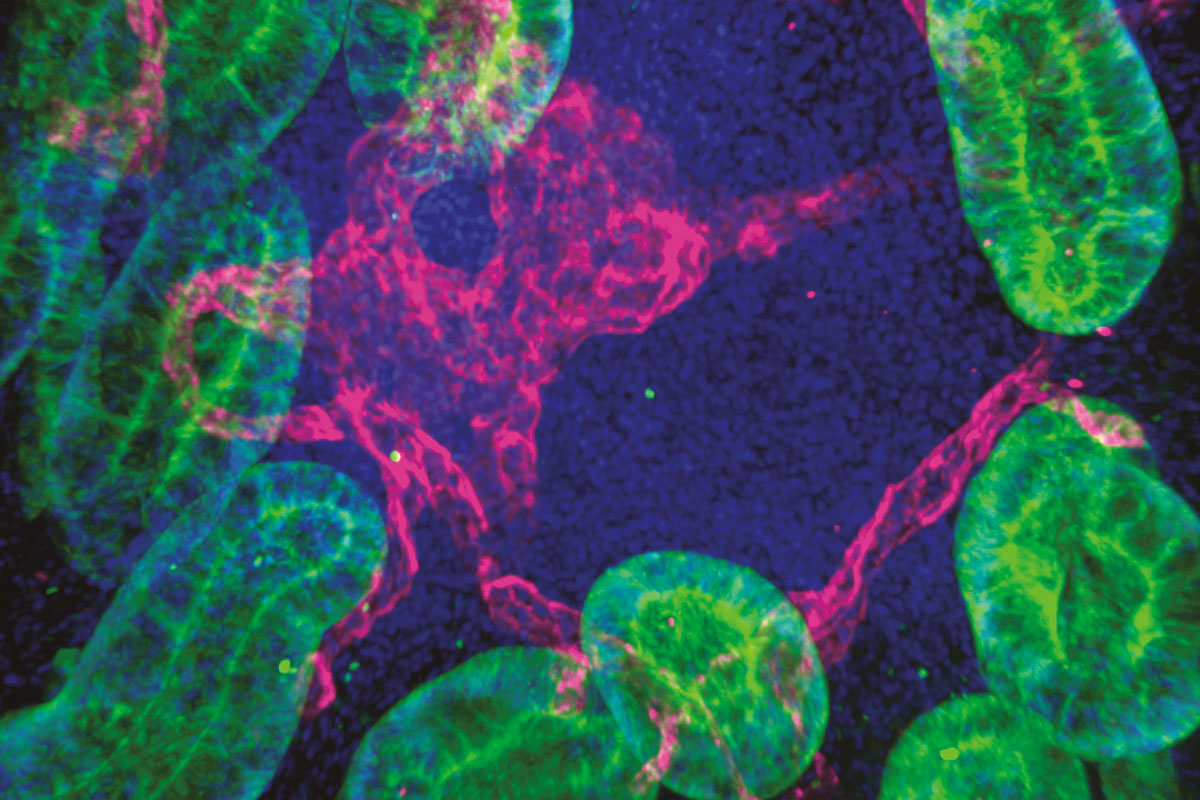

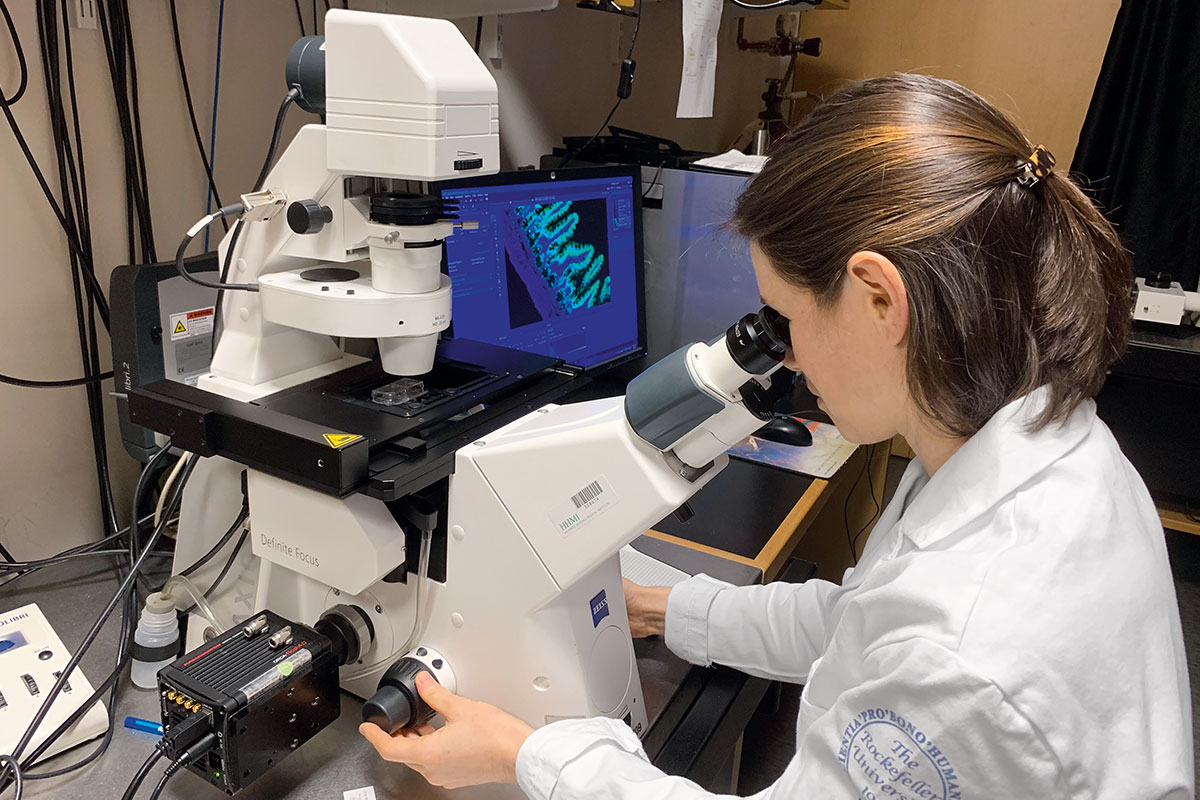

By Rachel NuwerRachel Niec is at her microscope, looking at a jellylike clump of cells from the lining of a mouse intestine. The view is chaotic: a jumble of immune cells, neurons, stem cells, and their surrounding vasculature, each component lit up in its own fluorescent color. Somewhere within the blob is a clue that Niec believes will lead her to a meaningful discovery, and perhaps suggest new ways to effectively treat inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Immunologists and gastroenterologists—Niec is both—typically think of IBD as a malfunction of the immune system. In the lawless landscape of the gut, immune cells must bravely sort the good bacteria from the bad—a daunting task. Any errors in their judgment can lead to runaway inflammation that irritates the delicate lining of the intestine and causes debilitating disease.

Yet the exact drivers of these conditions, likely a complex mix of genetics, biology, and environment, remain a mystery. For Niec, that means taking in the whole picture. It means looking at the epithelium—the gut’s version of skin—and considering everything that occurs there, from the role of microbial communities to the influence of the immune system to the processes of nutrient absorption.

“It’s not only overexuberant immunity or runaway microbiota; it’s more complicated,” Niec says. “To understand what’s going on, it’s helpful to study the entire tissue with all its constituents.”

Niec grew up in the Bay Area of California, the daughter of a middle school science teacher and a sound engineer. She spent weekends backpacking in Yosemite and exploring Northern California, where she learned to canoe and kayak in whitewater and wore out a dozen pairs of hiking boots. Niec’s budding interest in science was encouraged by her mother, who taught her to identify trees and birds and enthusiastically facilitated science experiments at home and in the woods. Niec attended Mills College, a small liberal arts school in Oakland known for its support of women’s leadership. She planned to become a science teacher.

But a summer internship in an immunology lab at the Center for Infectious Disease Research in Seattle shifted her thinking. Even as a volunteer intern, Niec was conducting important experiments, screening antibodies for their ability to recognize cells infected with HIV.

“This is when I started thinking about medicine,” Niec says. “It was my first experience generating scientific results that were going to impact the course of other people’s research, and eventually affect how we treat patients. It was satisfying to iterate experiments with a team, and it felt important because it related directly to human health.” She ended up spending three summers at the lab.

“Being able to make a difference in patients’ lives is a constant reminder of what my work in the lab is ultimately about.”

After graduating, she worked for a year as a Fulbright scholar at an HIV clinic for sex workers in Bali. Located in bustling Denpasar, the Kerti Praja Foundation—a three-story concrete building where Niec both worked and lived—saw up to 40 women per day. They came for reproductive health services but also for sewing classes and assistance securing microgrants. Niec had joined the team to help upgrade the clinic’s diagnostic capabilities and to support the doctors and join outreach workers in the field. She worked on programs to deliver clean water to the towns where patients lived, and she taught English.

Upon her return to the United States, Niec enrolled in a graduate program at the University of Washington in Seattle, and transferred to the Tri-Institutional M.D.-Ph.D. Program in Manhattan two years later when her adviser, Alexander Rudensky, moved to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. She finished her medical training at Weill Cornell Medicine, including a residency in internal medicine and a gastroenterology fellowship, and did her thesis work in Rudensky’s immunology lab.

Seeking a research project that would dovetail with her interest in gastroenterology, Niec embarked on postdoc training in the lab of Elaine Fuchs, a renowned stem cell biologist. “Elaine is among the best in dissecting stem-cell mechanisms, and merging our respective interests has really led to some fun questions,” Niec says.

Stem cells originating in the skin reside in so-called niches beneath the epithelium and can develop into diverse cell types. If you want to understand the complexity of the epithelium, the niche is the place to start. And if you want to understand the niche, Fuchs’s lab is the place to be. (Read more about the lab’s work on epithelial stem cells in “Stem cells are growing up”).

“Elaine and I recognized that there’s a real gap in our knowledge at the intersection of immunology and epithelial cells,” Niec says. “If we can build the tools to fill that gap, we will be able to ask questions that nobody else is positioned to ask.”

With Fuchs as her mentor, Niec enrolled in Rockefeller’s Clinical Scholars Program, which trains postdoctoral physician-scientists to integrate translational research and patient care. “This was the right kind of structure for me, because sometimes as a physician-scientist it can seem like you have each foot in a different world—the clinic and the lab. But in reality, these pieces are deeply connected,” says Niec. “I recently met with a patient in his later years of life who hadn’t responded to any of the conventional therapies for IBD, and had a wonderful response in a clinical trial. Being able to make a difference in this patient’s life, and the lives of others like him, is a constant reminder of what my work in the lab is ultimately about.”

Inflammatory bowel disease is a cluster of disorders that involve chronic inflammation of the digestive tract, including ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. These debilitating and at times life-threatening diseases affect over one percent of American adults, and their prevalence has increased over the past 20 years. No cures exist, and the available treatments are hit-or-miss. Although GI-related disorders can have genetic components and are influenced by the microbiota and other environmental features in a person’s gut, it’s at the intestinal epithelium—that messy soup of cells in Niec’s microscope—where the action happens.

“The key to treating these diseases will be to figure out who talks to whom in this ecosystem and how we can reset the communication networks,” Niec says.

Niec and her team are now working to understand what’s happening in the epithelial niche, what cellular actors are involved in immune signaling, and what they are saying. Because the architecture of the niche is so complex, the researchers use 3D imaging technology developed in Fuchs’s lab to simplify the picture.

Niec’s first significant finding derived directly from these imaging experiments, revealing that lymphatics—vessels that act as drainage canals for tissues—play a central role in communicating with stem cells in the intestine. The discovery is intriguing in part because IBD patients are known to have abnormal lymphatics, hinting that these structures might contribute to disease. Niec uses spatial transcriptomics—a technique to identify genes activated during communication between cells—to look for specific lymphatic signals that might be influencing the behavior of stem cells.

The work is an intellectual challenge, and the latest step on a longer journey that has been equal parts laboratory research and patient care.

“There are many untapped drivers of IBD to be targeted,” says Niec, who is a recent recipient of the prestigious Burroughs Wellcome Career Award for Medical Scientists. “Reaching the ultimate goal of translating these discoveries into treatments is what will make all the training worthwhile.”