just how dark does it have to get before our eyes stop working? Entirely dark, according to recent experiments. They suggest the human eye can detect the presence of a single photon, the smallest measurable unit of light, once it has been acclimated to the dark.

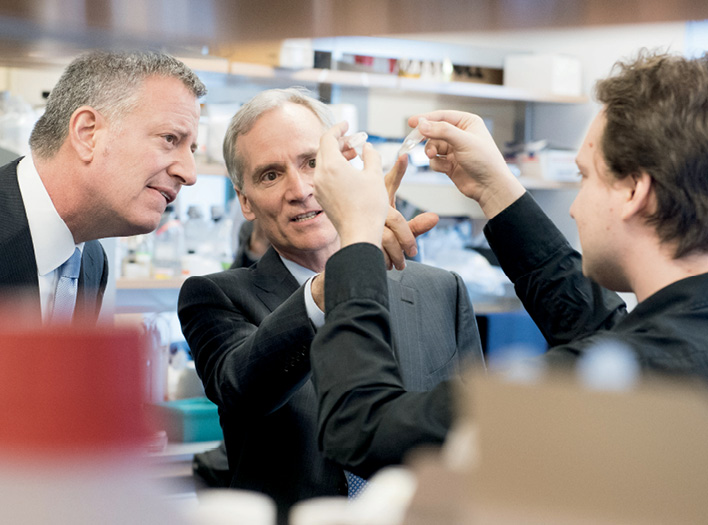

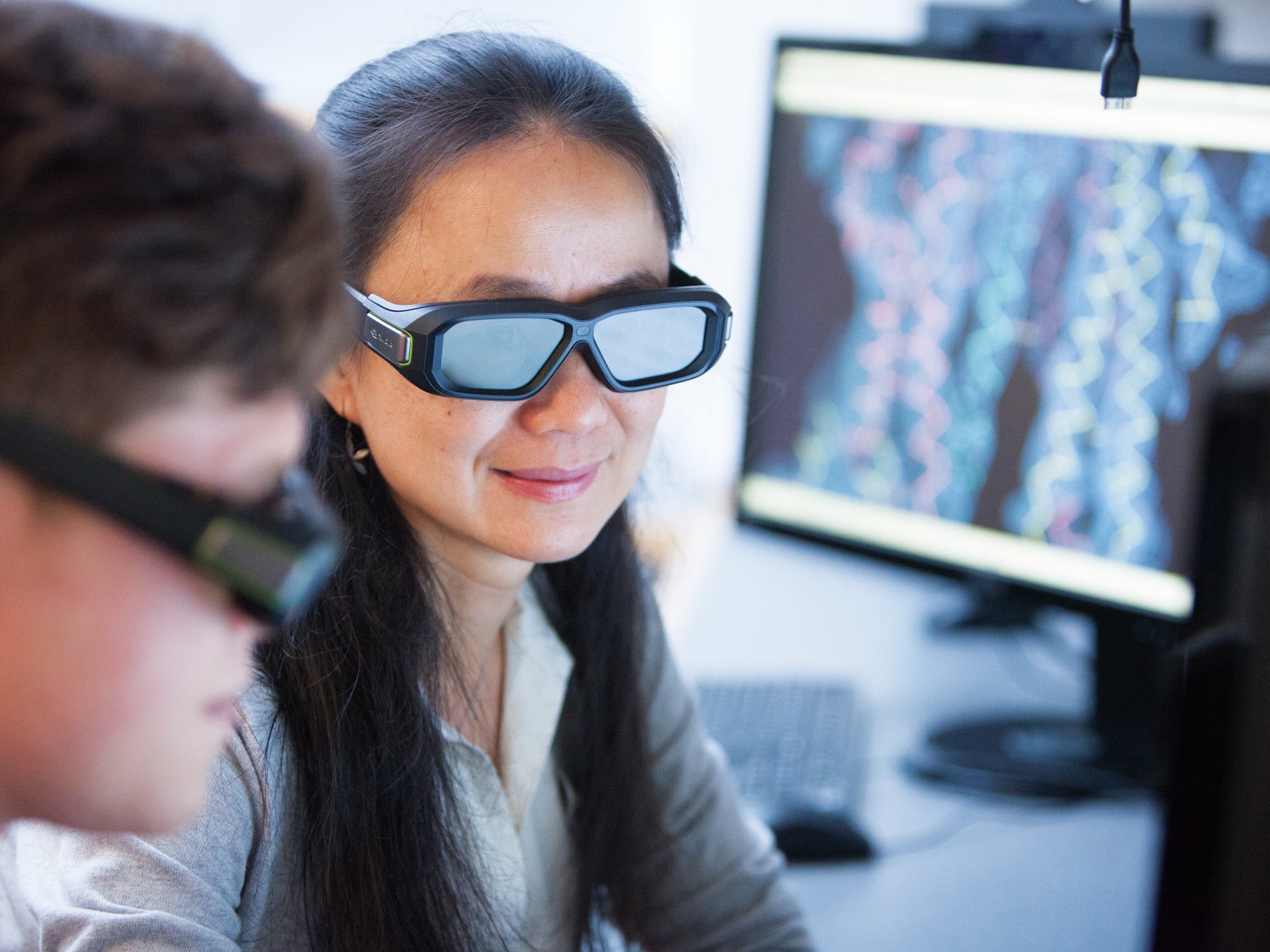

“If you imagine this, it is remarkable,” says Alipasha Vaziri, head of Rockefeller’s Laboratory of Neurotechnology and Biophysics, who conducted the research together with scientists at the Research Institute of Molecular Pathology in Austria. “A photon—the smallest physical entity with quantum properties of which light consists—is interacting with a biological system consisting of billions of cells. And the response that the photon generates survives all the way to the level of our awareness.”

Data

A 60-watt incandescent lightbulb emits roughly 8.2 quintillion photons per second.

Earlier studies had established that the human eye meets its limit at flashes of five to seven photons, but these experiments may have lacked the technology needed to produce such tiny, precise bursts of light. “It is not trivial to design states of light that contain exactly one or any other number of photons,” Vaziri says. His team was able to achieve this by implementing a combination of a psychophysics procedure and a quantum light source that can generate single-photon light states. The results, which combined data from more than 30,000 trials, were published in Nature Communications.