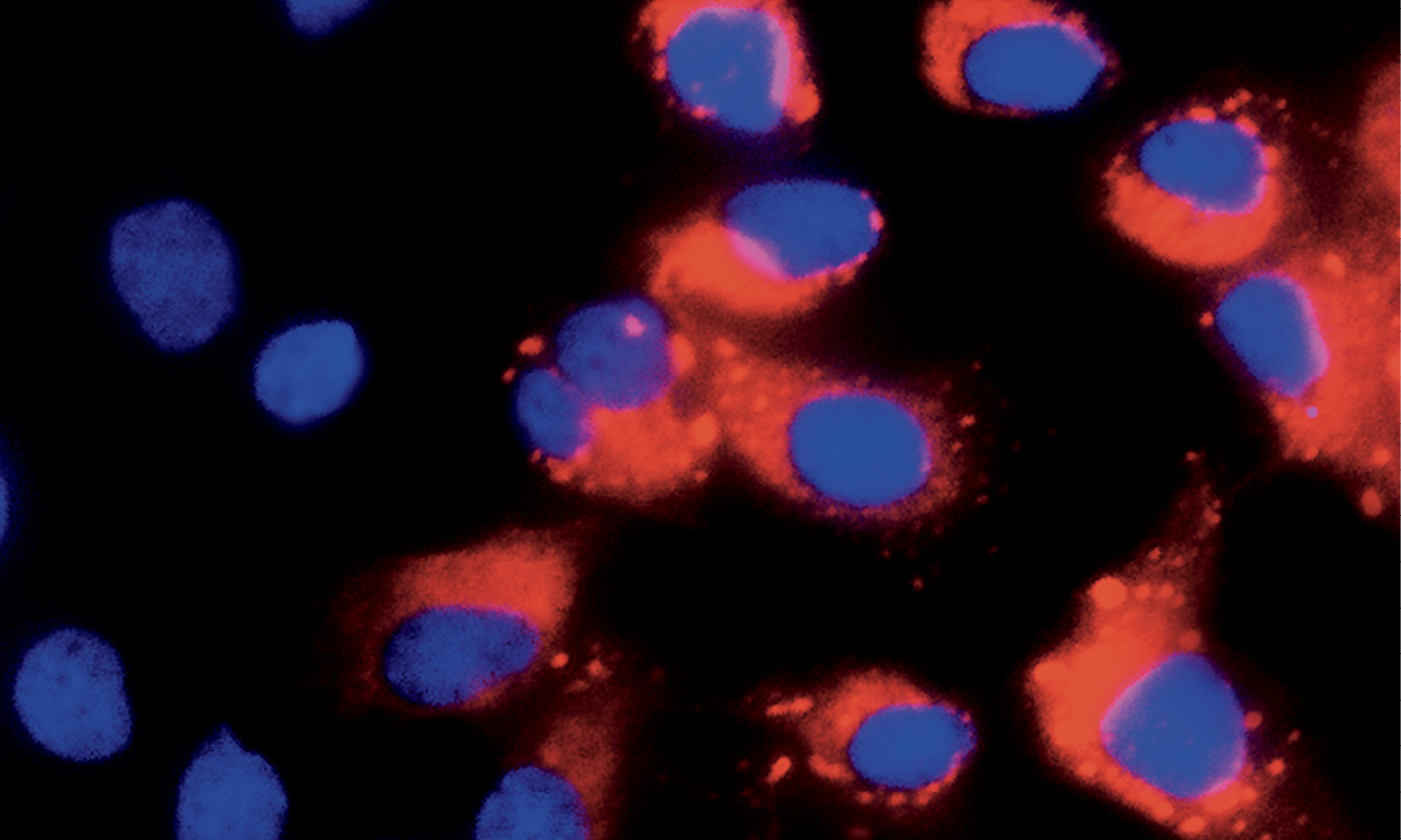

roundworms are not known for their personalities. But as it turns out, even microscopic organisms can have an independent streak.

Rockefeller’s Cori Bargmann, the Torsten N. Wiesel Professor, has shown that genetically identical C. elegans worms, including those that have been raised in perfectly identical environments, can behave quite differently. In experiments published in Cell, her team used cameras to document every movement made by 50 worms searching for food. While most worms adhered to a standard foraging pattern, a few took the road less wiggled, departing significantly from the typical route. The scientists concluded that neural development involves a certain element of randomness—neither nature nor nurture completely determines behavior. (Read more about Bargmann’s work in “Deep secrets,” here.)

Data

The maximum speed of a C. elegans worm is approximately 0.4 millimeters per second.

They also found a way to influence worm eccentricity by tinkering with the animals’ neurochemistry—specifically, by shutting off their serotonin production. Groups of C. elegans that lacked this chemical also lacked renegades: Every individual foraged the same way, in perfect synchrony.

Besides being boring, uniformity can be dangerous to a population. “From an evolutionary point of view, we can’t have everyone going off the cliff all at once, like lemmings,” says Bargmann. “Someone’s got to be doing something different for a species to survive.”