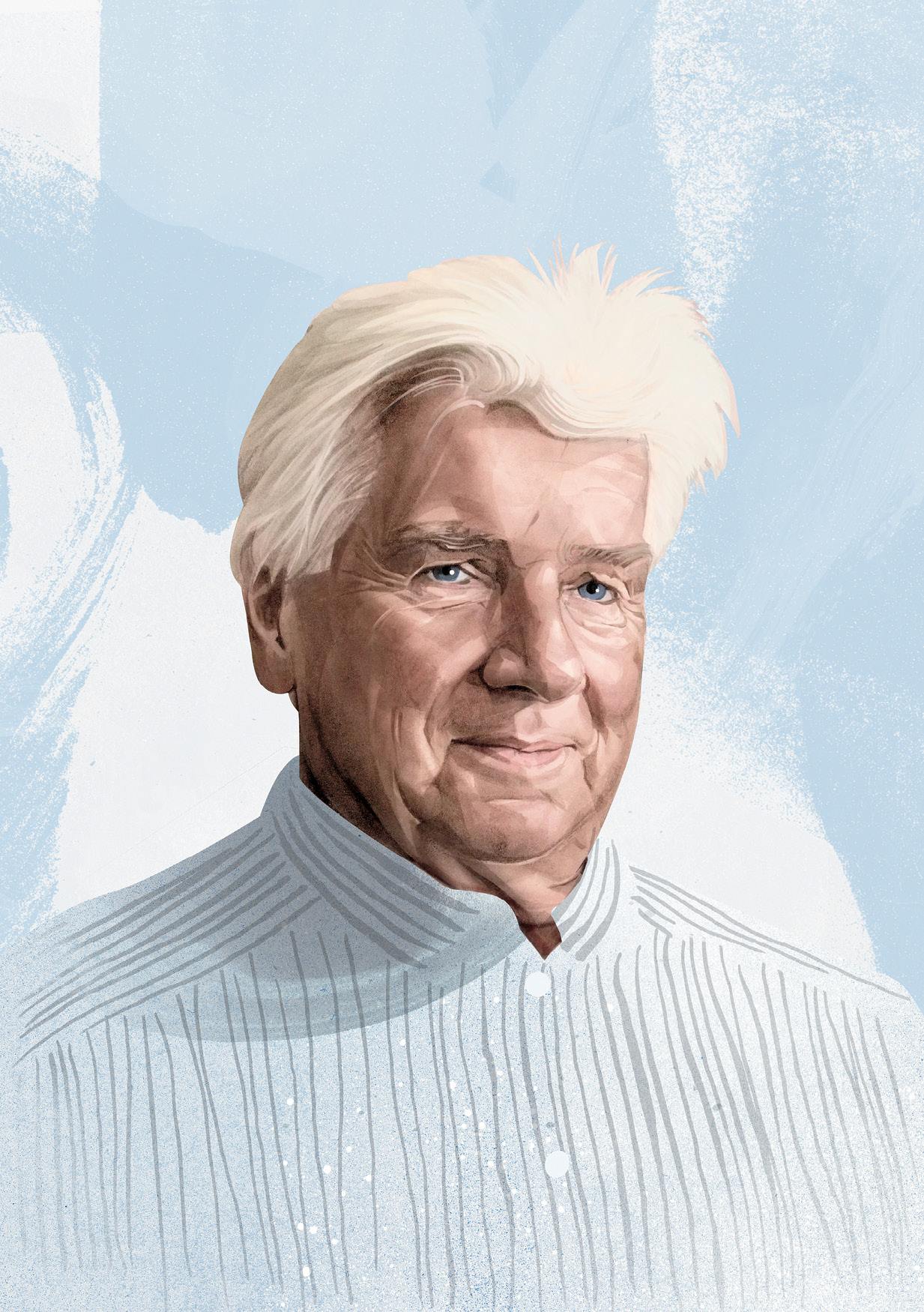

Interview

“I still feel the vibration.”

In memory of Günter Blobel, 1936–2018

By Eva Kieslerone of the most extraordinary days of Günter Blobel’s life was in December of 1974. Bundled up in the laboratory cold room, he spent hours attempting to divorce cells from their delicate membrane structures—something he had been trying to do, unsuccessfully, for almost two years. On this day, however, it happened: He was able to produce a viable membrane extract from dog pancreas and, for the first time, use this extract to simulate a biological process in a test tube.

The process was related to protein trafficking, a system that enables cells to organize billions of proteins so that each ends up in the right membrane-walled nook—those whose job it is to package DNA are ferried to the cell nucleus, for example, while proteins tasked with producing energy are sent off to mitochondria, the cell’s internal powerhouses. Blobel imagined that the system relied on each protein carrying a virtual zip code, a sequence that signals its destination.

Data

Blobel donated his Nobel Prize money for the rebuilding of the Frauenkirche, a baroque Lutheran church, and for the building of a new synagogue in Dresden.

It was a controversial idea that Blobel had arrived at somewhat intuitively. To prove it, he needed a persuasive assay, a way to break apart a cell’s protein-trafficking machinery and then reassemble its still-operational components in order to pinpoint which component does what. The 1974 membrane-manipulation exercise was a first step in developing this method, and although it didn’t yield much useful data in and of itself, the very fact that it had worked was a landmark.

“Günter’s work laid the foundation for the modern field of molecular cell biology,” says Richard P. Lifton, Rockefeller’s president. With his new methods to dissect cellular phenomena, Blobel helped set in motion a new phase in the study of life and disease, forever changing how biologists ask questions and seek answers.

In addition, his trailblazing insights into protein trafficking had far-reaching practical implications. “It led to important insights into normal physiology and numerous diseases,” says Sanford M. Simon, a Rockefeller colleague who once trained with Blobel, “and it helped launch new fields of biotechnology, such as methods to produce human proteins in other organisms.”

“Science is the only human endeavor that is for the entire mankind.”

Blobel, who died on February 18, was the recipient of many prestigious awards, though he liked to point out that no prize—not even the Nobel, with which he was honored in 1999—could compare with the thrill of science itself. “It’s very nice, and everybody claps, and you get a medal you can hang on the wall,” he laughingly told us last year. “But it’s not the equivalent excitement that you have when you discover the thing. That is why I am still in science—because I still feel the vibration of a new discovery.”

We conducted over four hours of interviews with Blobel in 2017, as part of an oral history project. Here are a few highlights:

On cellular evolution and the nuclear pore complex:

The arrival of the nucleus is one of the most important advances in the three and a half billion years of cellular evolution. The first two billion years were fairly boring, you could say. There were single cells, similar to our bacteria. But then, taking the genetic material and putting it into the nucleus, that was a very big revolution. It allowed the DNA to grow and be protected. But, it made it necessary to communicate between the nucleus and the cytoplasm.

You cannot just put it in a little capsule and say, here you are. There has to be bidirectional traffic. And the organelle that does it is called the nuclear pore complex. It looks like a little flower with eight petals, and has been photographed by thousands because it’s so beautiful. It has been looked at and electron-microscoped for 20 years. (Watch a modern rendering of the nuclear pore complex in “A molecular behemoth,” here.)

Data

Blobel’s lab discovered several components of the nuclear pore complex and elucidated the process by which molecules move through it.

On witnessing the 1945 bombing of the historic city of Dresden, at age nine:

We came in with this car that my older brother was driving, and suddenly I saw all of these towers, and the cupola of the Frauenkirche, and I was absolutely enchanted. I’ve always remained attached to this city, because I saw it in a completely intact way. A couple of days later, we were at the farm of relatives about 30 or 40 miles away from Dresden, and we saw the planes that came, and the bombing started about nine o’clock. We went out and looked, and the entire sky was red. Then I saw the city again when we tried to go back to Silesia, and it was just rubble.

On being a scientist:

Science is the only human endeavor that is for the entire mankind. Music or cultures are local, but the formula for water is the same in China as it is somewhere else. So it’s the only cultural pursuit of mankind, I think, that is universal.

Scientists should go out more, and should interact with the public, because the public doesn’t know the absolute beauty of science. I find it most fascinating that we, as we sit here, represent three and a half billion years of continuous cell division—of eternal life, if you wish.

Watch these and other clips, and photos of Blobel, here.