Our prehistoric past is a blur. Scientists are not sure, for example, exactly where the first Homo sapiens emerged around 200,000 years ago, or why our cousins, the Neanderthals, went extinct more than 150,000 years later.

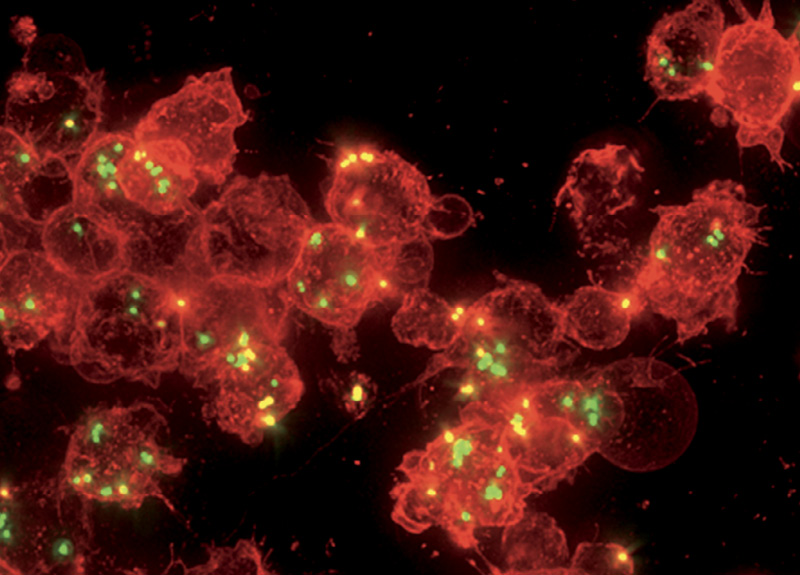

On the other hand, they do know quite a bit about our immune system’s historic battles, dating as far back as 11 million years. In studying DNA of orangutans, macaques, and other present-day primates, Rockefeller biologists have revealed how our hominoid ancestors conquered a retrovirus—a pathogen of the same class as modern HIV. This fresh DNA contains ancient traces of infection: when our predecessors contracted the retrovirus, their genomes were sprinkled with clippings of its genetic material. In some cases, the infected cell happened to be a sperm or egg cell, and the imprint got passed on for generations, creating a genetic fossil record.

Data

The human lineage and the gorillas’ parted ways around 10 million years ago.

“Analyzing viral fossils can give us a wealth of insight into events that occurred in our distant past,” says Paul Bieniasz, who led the research, published in eLife in April. Working with scientists at the University of Glasgow, his lab has compiled a near-complete inventory of such relics within the genomes of old-world monkeys and apes, and used it to investigate the warfare between primates and their microbial enemies.

In pinpointing the precise molecular maneuvers that eventually helped our ancestors get the retrovirus out of their systems, Bieniasz and his colleagues have learned about its weak spots—insights he says could potentially be harnessed to combat modern retroviruses, including HIV.