Loneliness is toxic. Not only can it make you feel sad or unfulfilled, but it has been linked to various health issues, from increased blood pressure to depression, cognitive decline, and cancer. The year 2020 was a case in point: Under shelter-in-place orders, Americans tended to be more anxious and depressed, had shoddier sleep quality, and, according to some estimates, put on more than half a pound per person every 10 days—a recipe for medical problems.

On the other hand, scientists have found that when people experience a sense of belonging—in a romantic partner, a pet, or at the local quilting club—they tend to live longer. So, what changes in the brain when we’re cut off from society?

Recently, scientists went looking for answers in a somewhat unexpected model, the seemingly primitive Drosophila melanogaster. Despite its tiny brain, the fruit fly is in fact a gregarious little creature with a highly complex social life. It forages, feeds, and explores its environment in the company of peers. It engages in elaborate mating rituals that, like human wedding traditions, are passed down through generations by social learning. And according to the new research, it suffers under lockdown.

Data

In a recent study, 36 percent of Americans reported feeling lonely “frequently” or “most of the time.” Young adults aged 18–25 and mothers with young children were among the most affected.

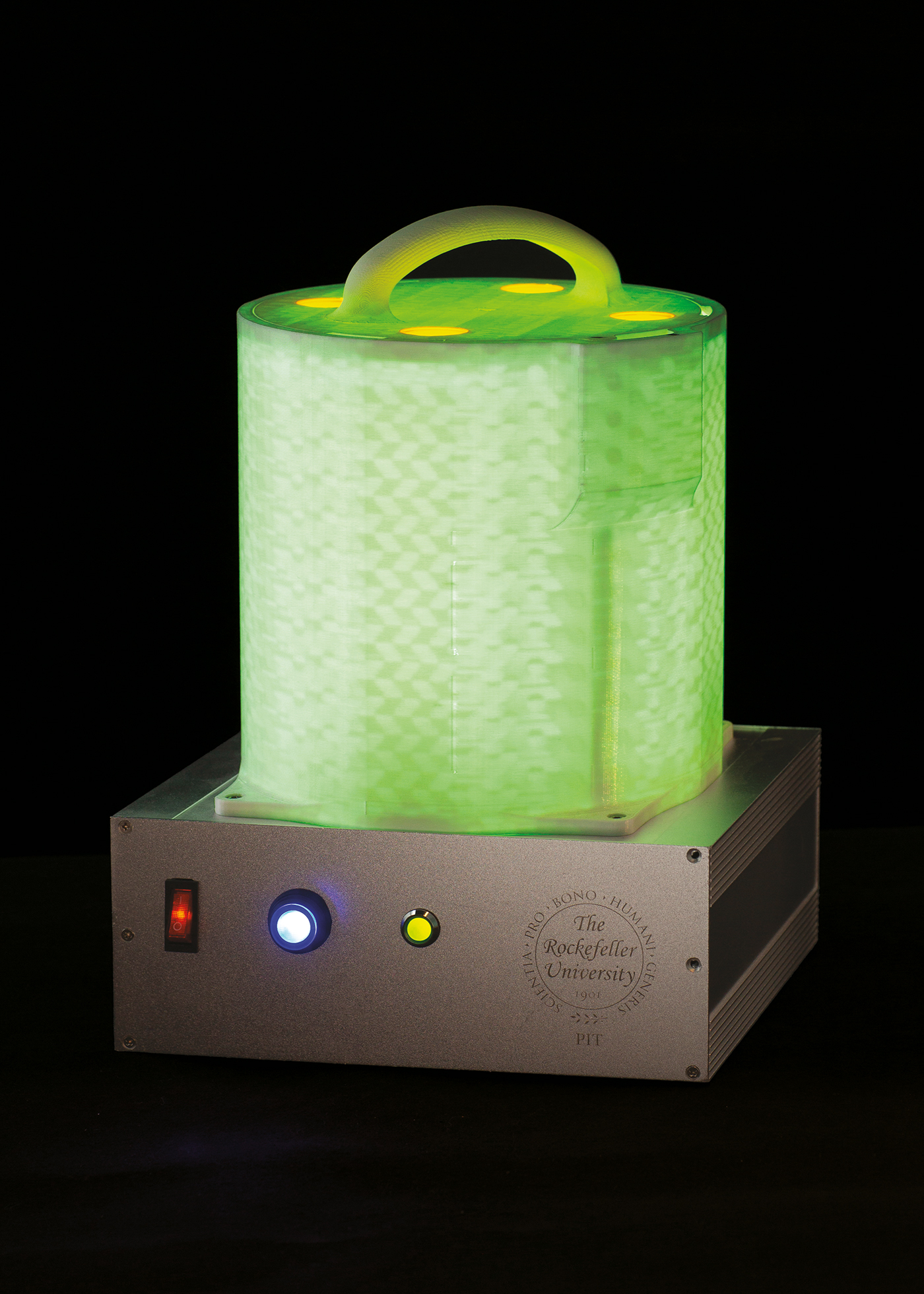

Wanhe Li, a research associate in the lab of Michael W. Young, let some flies abide on their own while congregating others in groups of various sizes. Seven days into the experiment, the solitary flies were sleeping less and eating more, just like isolated Homo sapiens. The control flies carried on sleeping and eating normally, however, as long as they had one or more companions.

“It may well be that our little flies are mimicking the behaviors of humans living under pandemic conditions,” says Young, who is Rockefeller’s Richard and Jeanne Fisher Professor and a 2017 Nobel laureate.

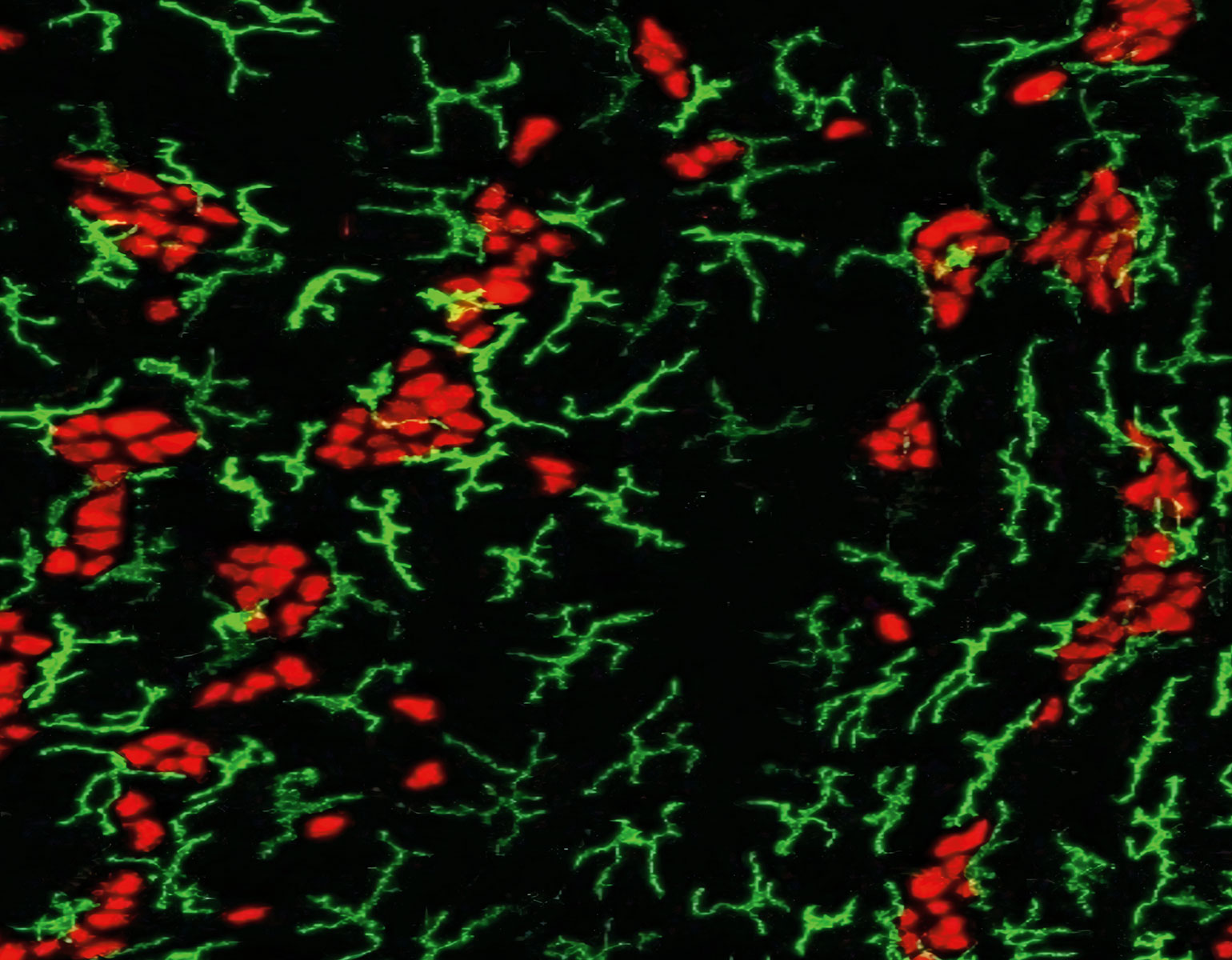

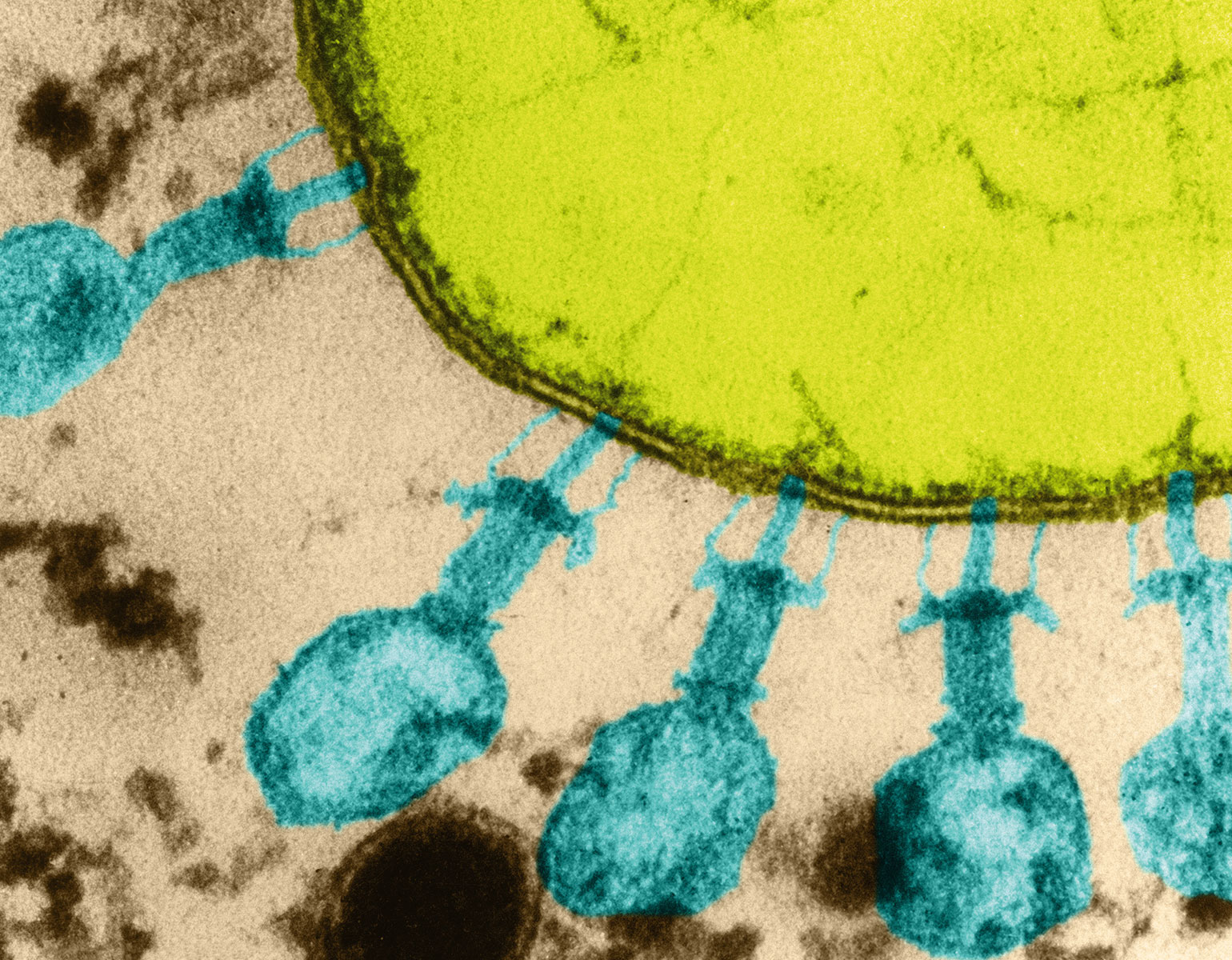

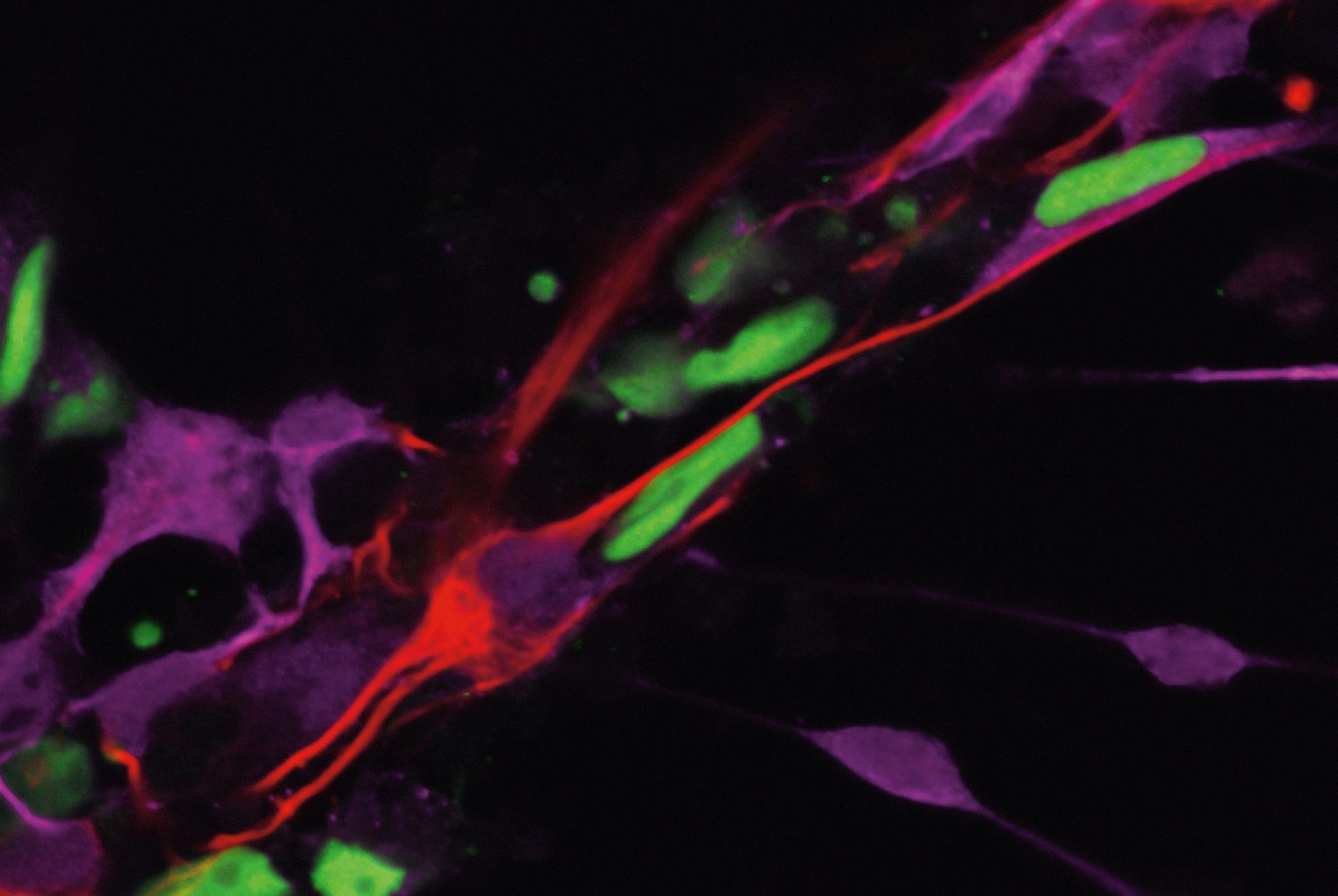

The scientists identified a small group of neurons that might be driving a fly’s loneliness response. When they shut down these neurons in genetically manipulated flies, the animals maintained normal sleep and feeding patterns, even after a week in exile. The findings, published in Nature, might inform research into the biology of social isolation in mammals, which is currently a black box.

“When we have no road map, the fruit fly becomes our road map,” Li says.